(Part 1 of 2)

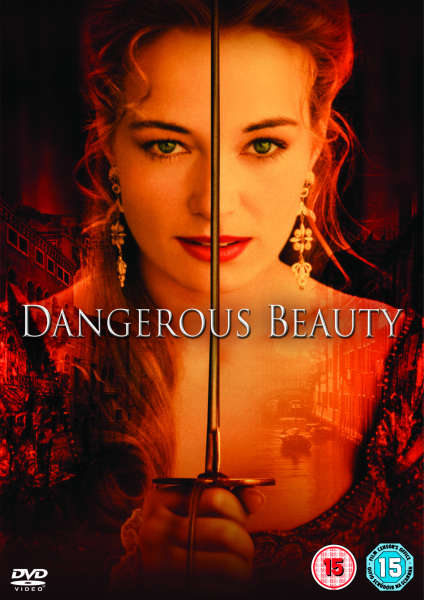

Some number of years ago, I viewed a film called Dangerous Beauty (1998), it having been recommended on a list of films every feminist should view. The film was a loose biography of Veronica Franco, a 16th century courtesan from Venice. It presents Franco as an adventurous, wild-hearted young woman faced with the choice of either becoming a courtesan or entering a convent because her family lacks the money to provide her with a decent dowry. She is initially repulsed by the proposal, but later accepts it as a Faustian bargain when she learns that becoming a courtesan would give her access to libraries, education, and study of the Renaissance arts. She comes to embrace and excel at her new profession, becoming both a hero to the people of Italy and the target of envious men, eventually leading to her being called before the Inquisition on charges of witchcraft.

The movie left me with a lot of questions about Franco and other courtesans like her whose profession allowed them, as women, access to education and engagement in the public sphere. I decided to do a paper on them for my Renaissance class at Trinity. Yes, that’s right, I thought writing a paper on people who f*** for a living would make for a fine and dandy topic at a conservative Christian school! Though, in retrospect, the subject matter was considerably cleaner than one of Mark Driscoll’s sermons.

I had a lot of questions as I embarked on my paper. Questions such as:

- Why did a society supposedly entrenched in the Christian sexual ethos turn so readily and openly to the arms of these “fallen women”?

- Why did courtesans enjoy a relative level of glamor, dignity, and success that transcended that of the prostitutes, their more common peers?

- In what ways did the Reformation and Counter-Reformation remedy the problem of prostitution, and in what ways did they fall short?

Christianity & Prostitution

Throughout much of Christian history, Christians’ attitude towards prostitution was one of tolerance. The human sex drive, and the male sex drive in particular, was viewed as inevitable, but men from the middle and upper classes tended not to marry until their late 20s, when they had taken time to establish themselves. Between that and clerical vows of celibacy, sex within the bonds of marriage was out of reach for a number of young men, and masturbation was discouraged. It was believed that for men to abstain altogether from sex was outright unhealthy. So Christians—and yes, that included Christian leaders and theologians—looked to prostitution as a solution to the dilemma. They figured that it kept down on rape and adulterous liaisons with “honest” married women. Thomas Aquinas likened prostitution to the sewer system of a beautiful palace. Sure, it’s vile and it stinks, but without it, the palace itself would overflow with excrement.

It’s interesting that even though women were stereotyped as lusty and unable to control their passions, the female sex drive was not viewed as a significant cause of prostitution. They reasoned that women expel their bodily fluids and release their sexual tension in part through menstruation and lactation, while men need ejaculation for the same. And masturbation wasn’t good enough, because reasons, so the only solution for the poor men was a seedy underbelly of impoverished hookers.

By the time of the Renaissance, prostitution was not just tolerated but regulated as a valuable tax source. In 1559, the Bishop of Polignano was caught with a Jewish courtesan by the name of Porzia. The Bishop “was sentenced to perpetual imprisonment whilst Porzia was exiled from Rome, having been publicly whipped, had her goods confiscated and her house ransacked.” [1] The general public expressed astonishment, but not over the bishop’s punishment. He had technically broken his vow of celibacy, and Christians weren’t supposed to have sex with Jews, so he deserved it. But Porzia was a public courtesan who always paid her tribute and as such, in the eyes of the most Roman citizens, had done nothing wrong. Porzia and the Bishop just happened to be two of the earliest victims of the Counter-Reformation and its changing attitude towards prostitution.

More on that in the next post.

———–

[1] Tessa Storey, Carnal Commerce in Counter-Reformation Rome (Cambridge: University of Cambridge Press, 2008), 1.