As part of my PhD coursework, I am currently enrolled in a class at TEDS called “Great Female Theologians,” taught by Fellipe M. do Vale. The class has been using Amy G. Oden’s In Her Words (1994) to read excerpts from women like Perpetua (c. 182–203), Macrina (324–379), Egeria (AD 4), Dhuoda (AD 9), Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179), Catherine of Siena (1347–1380), Juana Inés de la Cruz (1648–1695), Susanna Wesley (1669–1742), Jarena Lee (1783–1864), Phoebe Palmer (1807–1874), and Pandita Ramabai (1858–1922). The class has also supplemented with large excerpts from or entire books by Julian of Norwich (1342–c. 1416), Christine de Pizan (1364–1431), Teresa of Avila (1515–1582), Katharina Schütz Zell (c. 1497–1562), and Sojourner Truth (c. 1797–1883).

As part of my PhD coursework, I am currently enrolled in a class at TEDS called “Great Female Theologians,” taught by Fellipe M. do Vale. The class has been using Amy G. Oden’s In Her Words (1994) to read excerpts from women like Perpetua (c. 182–203), Macrina (324–379), Egeria (AD 4), Dhuoda (AD 9), Hildegard of Bingen (1098–1179), Catherine of Siena (1347–1380), Juana Inés de la Cruz (1648–1695), Susanna Wesley (1669–1742), Jarena Lee (1783–1864), Phoebe Palmer (1807–1874), and Pandita Ramabai (1858–1922). The class has also supplemented with large excerpts from or entire books by Julian of Norwich (1342–c. 1416), Christine de Pizan (1364–1431), Teresa of Avila (1515–1582), Katharina Schütz Zell (c. 1497–1562), and Sojourner Truth (c. 1797–1883).

One of the requirements for the class was that we select a woman in church history not in the class readings and do a presentation on her, to introduce the class to more women whom we haven’t had time to read. The presentation is open-ended; we’re welcome to do a painting, a poem, a song, etc. Students have given some very interesting presentations on Mary of Egypt (c. 344–c. 421), Héloïse (c. 1100–c. 1164), Christiana Tsai (1890–1984), Dorothy Sayers (1893–1957), and Flannery O’Connor (1925–1964), among others.

I chose to do my presentation on Walatta-Petros (1592–1642), an Ethiopian Orthodox saint and resistance leader who founded and served as abbess over seven monasteries and fought the attempted colonization and conversion of Ethiopia by Portuguese and Spanish Jesuits. A hagiography of her was written just thirty years after her death by one of her male disciples, “sinner and transgressor” Galawdewos. It has only been made available in English in 2015 by Wendy Laura Belcher and Michael Kleiner. A pared-down student edition with just Galawdewos’s text and an introduction by Belcher was made available in 2018.

The Life of Walatta-Petros is a fascinating text that presents its subject as a powerful, prophetic, apostolic, even quasi-messianic woman. Her birth is foretold to her father by a monk:

“I have seen a great vision with a bright sun dwelling in the womb of your wife . . . A beautiful daughter who will shine like the sun to the ends of the world will be born to you. She will be a guide for the blind of heart, and the kings of the earth and the bishops will bow to her. From the four corners of the world, many people will assemble around her and become one community—people pleasing God.” (6-7)

Her father is so pleased at her birth that he insists on holding her immediately despite the “unclean” nature of childbirth:

“Therefore, [her father] went happily and exultantly into the house of childbed, even though he was a great lord and it was not appropriate for him to enter into such a house. . . . The midwife said to him, ‘How can you hold and kiss a newborn who is all covered in blood?’ He responded, ‘Give her to me! Truly, there is no unclean blood or filth on this daughter of mine.’ . . . On account of all this, we consider blessed Walatta-Petros’s father and mother who brought forth for us this blessed and holy mother through whom we have found salvation.” (7–8)

The text repeatedly connects Walatta-Petros (whose name means “Daughter of Peter”) to male authority figures in the Bible such as Moses, Elijah, Peter, or Paul, thus suggesting that she is a prophet or apostle of sorts. For example:

“As Paul says, ‘You all are the house of the Lord.’ Just as the Lord gave Peter the keys to the Kingdom of Heaven, so he likewise gave to Walatta-Petros that those who follow her will enter into the Kingdom of Heaven. And as the Lord said three times to Peter, ‘Tend my sheep,’ so to her likewise he conferred the tending of his sheep in the pasture of meritorious spiritual struggle.” (8–9)

“She truly was worthy of this name of Walatta-Petros since the son of a king becomes a king and the son of a priest becomes a priest; and just as Peter became the head of the apostles, she likewise became the head of all religious teachers. Just as Peter could kill and resurrect through his authority, she likewise could kill and resurrect. She became a god by grace, as scripture says, ‘You are gods, all of you are children of the Most High.’ O glory, glory of such dimensions! O sublimity, sublimity of such greatness! While she was a human being like us, to her it was given to be a god.” (9)

Obviously, there is some Eastern Orthodox theosis / deification at play here.

The text touches on a number of issues women typically struggle with. One of these is the struggle for beauty:

“But the outer beauty of her appearance was surpassed by the inner beauty of her mind. Listen, my loved ones: What should make us boastful of the beauty of our appearance, which changes and decays? Is a human being justified before God by his beautiful appearance, or damned by his ugly aspect? . . . God, by contrast, favored Leah—who was despised because she was ugly in appearance and had bleary eyes—by opening her womb, and so she gave birth to Judah from whose seed Christ was born . . . Because of this, we should not boast about the beauty of our looks, nor need we be ashamed of the ugliness of our appearance, since that which is perishable should clothe itself with that which is imperishable.” (9–10)

Walatta-Petros was married off young to the king’s right-hand man, Malkiya-Kristos. She had three children with him, but none survived. She soon fell into conflict with her husband when he converted to “the filthy faith of the Europeans” alongside King Susinyos. Belcher explains that a number of Ethiopian court members and officials converted for political reasons, but their wives and daughters would not submit to them and refused to follow them, so that the Ethiopian resistance to European colonization was female-led. (eBook loc 70)

At age 24, while her husband was away on a military campaign, Walatta-Petros ran away from him to become a nun. He pursued her. When it became clear she would fall into his hands again, she used scriptural texts to liken her situation to marital rape: “God’s will be done! He can save me; to him nothing is impossible. He who saved Sarah from the hands of Pharaoh, the king of Egypt, and from the hands of Abimelech, king of Gerara, he will also save me. He who saved Susanna from the hands of the old men, he will also save me.” (17) Just for comparison, marital rape was not a crime in all 50 United States until July 5, 1993, yet Walatta-Petros knew all the way back in the 17th century that it was wrong.

Her husband was abusive to her upon catching up to her (18) and she was forced to reconcile, but the reconciliation was short-lived. The king had the Ethiopian Orthodox patriarch murdered and sent his vestment to Malkiya-Kristos as a reward. Walatta-Petros was furious. She began withholding sex from her husband until he relented and let her go, this time for good.

She developed a close friendship with a woman named Eheta-Kristos who also left a husband and daughter to become a nun: “As soon as our holy Mother Walatta-Petros and Eheta-Kristos saw each other from afar, love was infused into both their hearts, love for each other, and, approaching, they exchanged the kiss of greeting. Then they sat down and told each other stories about the workings of God. There was no fear or mistrust between them. They were like people who had known each other beforehand because the Holy Spirit united them.” (26)

In 1622, Emperor Susinyos I declared Roman Catholicism the official religion of the Ethiopian empire. Walatta-Petros objected to the “filthy faith of the Europeans” and especially the hypostatic union:

“After this, King Susinyos began to make changes and established the filthy faith of the Europeans, Catholicism, which says: Christ has two natures, even after he, in his divine and human natures, became one and he became the perfect human being. Thereby, Susinyos repudiated the holy faith of Alexandria, which says as follows: Christ became the perfect human being; he is not split or divided in anything he does; he is one Son. In him there is only one aspect, one essence, and one divine nature, namely, that of God the Logos.” (29)

Because of Walatta-Petros’s work in leading the resistance, the king wanted to kill her “or at least [cut off] her breasts” (34). Her husband, who still loved her, intervened and proposed exile instead, to which the king agreed. On her way out to exile, her boat was attacked by a hippo, but Walatta-Petros remained calm and calmed her disciples. The hippo eventually fled. (36)

She later received a visit from Jesus Christ, who told her of the imprisonment she was about to suffer, the people she would convert, and the great things she would do. She told him, “How will I be able to save others, I who cannot save myself? Am I not mud, and a pit of filthy sludge?” Jesus responded, “Even mud, when it is mixed with straw, becomes strong and enduring and can hold grain. You, too, I will make likewise strong.” (45)

She continued to make trouble for the king from exile, so he captured her and planned to kill her again. And again, her husband intervened and suggested she be forced to listen to Roman Catholic preaching and teaching instead, in hopes that she would convert.

“Then they began to try to persuade her with many clever tricks to abandon the true faith of the Orthodox pope Dioscoros and adopt the filthy faith of the Catholic pope. . . . Three renowned European false teachers came to her and debated with her about their filthy faith, which says, ‘Christ still has two natures after the ineffable union of his humanity and divinity.’ She argued with them, defeated them, and embarrassed them. . . . Rather, she laughed and made fun of them.” (52–53)

“Then they began to try to persuade her with many clever tricks to abandon the true faith of the Orthodox pope Dioscoros and adopt the filthy faith of the Catholic pope. . . . Three renowned European false teachers came to her and debated with her about their filthy faith, which says, ‘Christ still has two natures after the ineffable union of his humanity and divinity.’ She argued with them, defeated them, and embarrassed them. . . . Rather, she laughed and made fun of them.” (52–53)

Walatta-Petros was sent to be imprisoned and tortured for three years by the very unfortunately-named “Black man.” He tortured her, tried to seduce her, then tried to rape her. “Then Satan entered into the heart of the Black man so that he laid his eyes on Walatta-Petros: he began to make advances toward her, as men do with women. When she rejected him, he used a cord to tie her back to the house post and secured her in that position.” He tried to burn her but was unable to start the fire. Later, when he had it in mind to sexually assault her, an angel with a drawn sword protected her (57–58). For her own part, Walatta-Petros was kind to the Black man and eventually converted him with her kindness (61–62).

After being released, she traveled around, founding seven monasteries and performing miracles. Eventually her resistance was successful and the king converted back to Orthodoxy, while Roman Catholicism was mostly vanquished from the land.

With the patriarch still not replaced, Walatta-Petros attempted to appoint a man deacon in order to administer the Eucharist, but he questioned her authority.

“Furthermore, he disdained her and held her in contempt, saying in his heart, but not with his mouth, ‘What is it with this woman who gives me orders, acting as if she were a spiritual leader or a monastic superior? Does not scripture say to her, {We do not allow a woman to teach, nor may she exercise authority over a man?}’” (80–81)

Walatta-Petros responded by killing him (with prayer) and resurrecting him to teach him a lesson, whereupon he was a changed man. Galawdewos explains:

“So it is not acceptable for people to speak ill of and abuse those whom God has set up as leaders and appointed, in keeping with what scripture says: ‘Do not speak ill of your people’s leader.’ In the past, when Miriam and Aaron had secretly spoken ill of and abused Moses, leprosy sores had appeared on Miriam and she had been expelled from the camp of the Israelites for seven days until they had confessed with their mouths and openly declared their sins, with Aaron saying to Moses, ‘We have sinned because we have spoken ill of God. Please, pray for her so that this leprosy disappears from her.’ So Moses prayed for Miriam, and she was healed. This story of [this man] is similar.” (83)

Another example of men challenging her authority:

“Some resentful theologians arose, however, giving vent to their resentment against our holy Mother Walatta-Petros with satanic zeal when they saw that all the world followed her, that she was greater than and superior to them, and that they ranked below her. . . . Therefore, they said to her, ‘Is there a verse in the scriptures that states that a woman, even though she is a woman, can be a religious leader and teacher? This is something that scripture forbids to a woman when it says to her, {Regarding a woman, we do not allow her to teach. She may not exercise authority over a man.}’ With this argument, they wanted to make Walatta-Petros quit—but they did not succeed. . . . At that point, Father Fatla-Sillasé, the teacher of the entire world, said to them, ‘Did God not raise her up for our chastisement because we have become corrupt, so that God appointed her and gave our leadership role to her, while dismissing us? For this reason, you will not be able to make her quit. It is just as Gamaliel said in Acts, {Leave these men alone and do not harm them. If what they put forward is of man, it will pass and come to naught. But if instead it is from God, you will not be able to make them quit. Do not be like people who quarrel with God.}’ . . . In the same way also, the resentful theologians were unable to make our holy Mother Walatta-Petros quit because God had authorized her. If her teaching had not been from God, her community would not have held up until now, but would quickly have disappeared. Through its continued existence, it is evident that her community is from God.” (109–10)

I find it interesting that Father Fatla-Sillasé’s defense of Walatta-Petros was virtually identical to the explanation many complementarians offer for Deborah (Jdg 4), that she was only called to leadership and authority because “no worthy men” could be found. In this case, the men were unworthy because of their capitulation to Roman Catholicism, so Walatta-Petros was called. The text does not challenge the idea that 1 Tim 2:12 forbids women from teaching, preaching, or exercising authority; it simply insists that special exceptions can exist.

One of the miracles Jesus granted Walatta-Petros was early menopause (74–75). Like I said, this text deals with a surprising number of issues that impact women: childbirth, beauty, sexual assault, divorce, and friendships between women. There is also an entire chapter wherein Walatta-Petros condemned other nuns for lesbian relationships (Chapter 86, “Our Mother Sees Nuns Lusting After Each Other”).

After founding and leading seven monastic communities of both men and women with no male authority figure directly over her, Walatta-Petros prepared to die at the age of 50. She appointed Eheta-Kristos as her successor, with the text likening this to Elijah appointing Elisha (133–34). She died on November 23rd, 1642, and the text claims there were 27 miracles following her death through the end of the year. Ethiopia stands as one of the few non-European countries that was never colonized by Europe, in part thanks to Walatta-Petros’s resistance.

Belcher states The Life of Walatta-Petros is the earliest book-length biography of an African woman, and the only one written from an African perspective. For my own part, I found the text remarkable. I’m not sure I’ve ever read anything like it in church history in terms of its thorough presentation of a woman as an apostle, prophet, and authority figure over both women and men. Acts of Thecla is somewhat similar, but only a few chapters long, and Thecla primarily ministers to women.

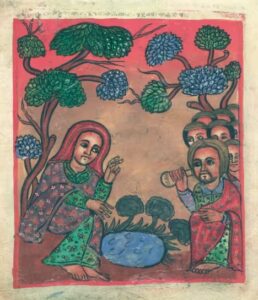

Many figures in church history are painted with their right hand raised in a teaching gesture, but this can also symbolize the hypostatic union, which Walatta-Petros rejected. She did not disagree that Christ is both fully divine and fully human, but the Ethiopian Orthodox church has a different take on how that works. In one of the paintings of her, she has the two fingers on her left hand raised in rebuke of the Roman Catholic priests trying to convert her, so I have painted her with the left hand raised.

(Also, I am NOT a painter. This is only the fourth painting I have ever done, and the first time I have tried to paint a real, specific human. She deserves to be painted by a far more skilled hand than mine.)

Anyhow, I hope you’ll give this fascinating account a read!

UPDATE: As of March 2024, I have published a short article on Walatta-Petros with Mutuality. You can download that from my Academia page here.

—————-

Galawdewos. The Life of Walatta-Petros: A Seventeenth Century Biography of an African Woman, Concise Edition. Translated and edited by Wendy Laura Belcher and Michael Kleiner. Kindle edition. (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2018).